Clarifications about the new Copyright Directive

On Sept. 12, the European Parliament passed the new Copyright Directive for the European Single Market.

This marks the beginning of the three-party negotiations necessary before the final approval of the Directive, which will be subject to vote soon, at the beginning of 2019. If the final version after these negotiations passes, each EU country shall have a maximum of two years to adapt and enforce the Directive.

- Which means: If you live anywhere inside the EU, this Directive will have a direct impact on your country’s Copyright Law no later than by 2021.

In this article, we’re going to go through some of the adopted texts, and we’ll try to do it in a simple and objective way. There’s been much debate around the changes done to the original proposal, about how this amended Directive will impact companies, creators, and Internet users in general inside the EU. We would like to add our own perspective to the debate, clarifying some doubts, and battling what we consider to be disinformation.

In this summary, you’ll find all you need to know about the Directive, as a creator, and as an Internet user.

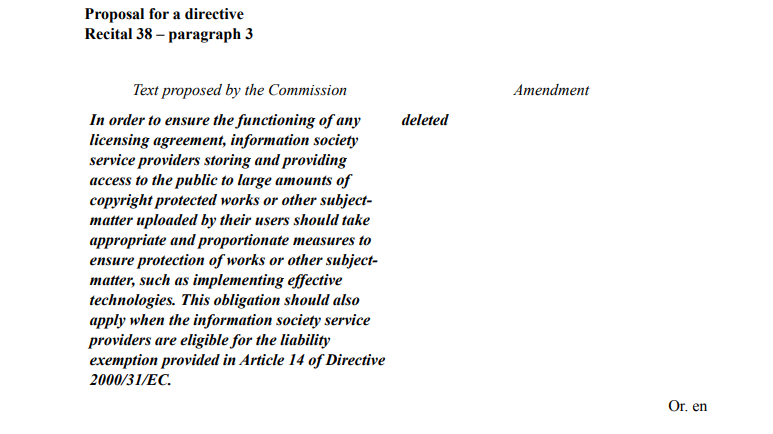

Content filters are not mandatory.

Unlike what’s been reported by many media, this part of the former text of the Directive has been deleted. Instead, there is an amendment that forces online content sharing services to negotiate license agreements with rightsholders, content providers, or collecting management organisations. (p. 57)

“Online content sharing services.” Definition.

It is relevant to highlight the definition of these Services under this Directive, to understand who will be affected by it:

“The definition of an online content sharing service provider under this Directive shall cover information society service providers one of the main purposes of which is to store and give access to the public or to stream significant amounts of copyright protected content uploaded / made available by its users, and that optimise content, and promote for profit making purposes, including amongst others displaying, tagging, curating, sequencing, the uploaded works or other subject-matter, irrespective of the means used therefor, and therefore act in an active way.” (Amendment 143, p. 29-30)

One can interpret that, according to the Directive’s texts, the liability for uploading copyrighted content will lie on the service, and not its users. Online content sharing services (hereafter Services) won’t benefit from liability exemption. (p. 29)

On the other hand, projects such as Wikipedia or other online encyclopedias, for example, would be exempt. So would be free software repositories, storage cloud services for individual users, research projects, etc.

Content withdrawal should be possible, but not indiscriminate.

According to the Directive, there must be good faith from all parties when it comes to withdrawing copyrighted content from online platforms.

This means, first of all, that users should be able to place claims and request the withdrawal of their content. But it also means that there should be a mechanism for those who uploaded it in the first place to answer back, in case the request is unfounded. Content withdrawal can’t be automated or arbitrary, and it shall take into account possible copyright exceptions. (p. 57)

In the text, there’s a direct mention to exceptions and legitimate use of content based on each country’s laws:

“When defining best practices, special account shall be taken of fundamental rights, the use of exceptions and limitations as well as ensuring that the burden on SMEs remains appropriate and that automated blocking of content is avoided.” (p. 58)

A typical copyright exception case would be the right to quote or reference a text in a research essay, for example.

Press and hyperlinks.

There are several instances where the Directive clearly states that hyperlinks will still be allowed as a way to link to news shared by the media. What is going to be limited, though, is the use of the specific content of the news, such as fragments of text or images, without a license.

It will still be allowed to:

- Copy a few words from the original text, although it’s unclear how many.

- Share objective data from the news, using different words.

- Share information as an individual.

Services will have to reach agreements with the media to compensate for any use they might make of their texts and images, and for the benefits generated by this use. Also, a proportional part of those benefits should go to the original authors of the works that are being used. (p. 55)

“[…] This protection does not extend to acts of hyperlinking. The protection shall also not extend to factual information which is reported in journalistic articles from a press publication and will therefore not prevent anyone from reporting such factual information”(p. 25)

Education exceptions.

The Directive features several texts on the use of copyrighted works for educational purposes, which we recommend to read attentively to any professional working in this field. (p. 7-12) For example, education centres and certain cultural heritage institutions are subject to a liability exception for text and data mining:

“Educational establishments and cultural heritage institutions that conduct scientific research should also be covered by the text and data mining exception, provided that the results of the research do not benefit an undertaking exercising a decisive influence upon such organisations in particular.”

Yet, the exception to use certain content and then reproduce it will affect only public education centres, or non-profit education iniciatives:

“The exception or limitation provided for in this Directive should therefore benefit all educational establishments in primary, secondary, vocational and higher education to the extent they pursue their educational activity for a non-commercial purpose.”

It’s worth noticing that all Member States will be able to implement their own model limiting the exception to the availability of certain licenses. In order to avoid legal uncertainty, though, the State’s licensing schemes must be clear, easily available, well-known to educational establishments, and they must “cover at least the same uses as those allowed under the exception”. (p. 11) The Directive points out that licenses could take different shapes, such as collective licensing agreements, to save educational establishments the hassle of having to negotiate individually with rightsholders.

This model would allow more control in each State over what content can be used freely for teaching purposes.

European fair use?

Amendment 20 introduces a new definition which sounds oddly familiar. It reminds of the “fair use” concept of the USA’s Copyright Law.

In case you don’t know it, in this article we explain what “fair use” is.

If the text is approved, this exception would allow to re-purpose pieces of copyrighted work in ways that don’t fit into today’s typical copyright exceptions, such as parodies or quoting. Remixes, mashups, or fanarts, for instance, would benefit from an increased legal certainty.

“A situation of this type creates legal uncertainty for both users and rightholders. It is therefore necessary to provide a new specific exception to permit the legitimate uses of extracts of pre-existing protected works or other subject-matter in content that is uploaded or made available by users.

Where content generated or made available by a user involves the short and proportionate use of a quotation or of an extract of a protected work or other subject-matter for a legitimate purpose, such use should be protected by the exception provided for in this Directive.

This exception should only be applied in certain special cases which do not conflict with normal exploitation of the work or other subject-matter concerned and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the rightholder. For the purpose of assessing such prejudice, it is essential that the degree of originality of the content concerned, the length/extent of the quotation or extract used, the professional nature of the content concerned or the degree of economic harm be examined, where relevant, while not precluding the legitimate enjoyment of the exception.

This exception should be without prejudice to the moral rights of the authors of the work or other subjectmatter.” (Amendment 20, p. 14-15)

Holders of related rights.

Negotiations between authors and third parties also will be affected by the Directive. This point should interest you if you have any licensing contracts, or if your works are interpreted, translated, performed… by other artists.

- Contracts shall specify clearly how the author will be compensated for the online exploitation of their works.

- Long duration contracts can be renegotiated, taking into account the new benefits generated by the works’ digital exploitation. This only applies if such benefits, according to new agreements, are higher than what was originally estimated.

- Authors and performers will be allowed to revoke exclusive licenses if there’s a lack of transparency between them and the transferee or licensee, or if their work hasn’t been exploited within a reasonable time frame. Revoking the license will be possible in this case, after exhausting all other options. (p. 37)

Transparency and collective management organizations.

Collective management organizations are directly addressed in several instances of the texts, highlighting their role as mediators. Among other things, the Directive will force these organizations to offer transparent, periodic, comprehensible information about their benefit distribution practices. This change seems necessary in view of how collective management organizations will be essential to ease licensing agreements between Services and rightsholders.

Also, the Directive stresses that authors have the right to withdraw specific works from the licensing mechanisms of these organizations.

Nothing is final until 2019.

We’d like to remind you that all of this is still pending negotiations and that each Member State will adapt the Directive in a different way, although the intention is to create a harmonized system. We’ll report again if the final version Directive is approved, especially if the text goes through relevant changes. Later on, you should read the specific texts adapting the Directive in those countries relevant to your work.

Finally, we apologize if there’s any inaccuracy, or if we have wrongly interpreted any part of the Directive. Such a broad text can cause uncertainty, and there’s no doubt that its practical adoption will bring even more challenges if it passes.

If you believe something should be further clarified or corrected, please, don’t doubt to leave your opinion in the comments below. Our intention is to make an honest, detached summary of the facts, so you can have the best possible information.

Authors: Mario Pena and Marta Palacio, Safe Creative.

References:

- Texts adoptades (provisional edition).

- Amendments. En inglés.

- “EU Parliament Approves Watered Down Copyright Directive” | Copyright and Technology.

- “What New EU Copyright Law Will Mean for Media, Tech Companies and Users” | The Hollywood Reporter.

- “The EU Copyright Directive Won’t Kill The Internet But It Will Kill Startups” | Forbes.

Photo by Christian Wiediger on Unsplash.